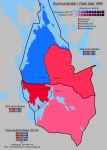

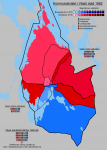

So I've now been able to trace the boundaries of the city back to the municipal reform in 1863, which created two municipalities to cover what had formerly been the Växjö cathedral parish: the City of Växjö (

Växjö stad), which covered the city itself and its land possessions within the parish, and the Växjö Rural Municipality (

Växjö landskommun), which covered the rest of the parish, including the lands of the episcopal see as well as the seven villages of Kronoberg, Araby, Hov, Östregård, Hollstorp, Skir and Telestad.

As you can tell, this created some slightly odd borders, as the city owned significant tracts of land along the highways west and north of it, enough in fact to split the rural municipality in half. Borders were complicated even further when the Royal Kronoberg Regiment (I 11) established a cantonment in the western rural part of the city in 1919, which detached a large area from the city council's ownership and moved it into state control. This didn't formally change the municipal boundaries, but it did have a significant effect on the history of Växjö as a city.

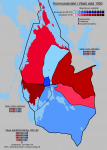

Despite being a cathedral city and the only city for dozens of miles in any direction, Växjö in the 19th century was a profoundly sleepy place, with only a couple of thousand inhabitants. The only things it had to recommend it were its grammar school and its role as a county town, and teachers and bureaucrats came to dominate local government in the early years. As urbanisation began to take hold all around the country, and as the cantonment was established, it began to slowly grow, and before too long it was spilling over into the rural municipality. East of the city centre, the city's jurisdiction ended immediately behind the cathedral, but a large suburb began to grow up in Östregård in the first years of the 20th century. In order to implement a city plan and various public safety laws, which normally weren't possible to apply in rural municipalities, Östregård decided in 1919 to form a

municipalsamhälle, a small ad-hoc council set up specifically to administer those laws. The borders of this council were set up to hug the edges of the settlement, leaving the episcopal estate as a near-exclave of the rural municipality in what was fast becoming the middle of the city. Remnants of this can still be seen today, as the bishop's pastures remain largely undeveloped. There's some allotments, and the northern half of it would be taken over by the new grammar school built in the 1950s, but there are in fact still significant areas of pasture in the middle of Växjö.

Until this point, elections in Växjö had been simple affairs. The voters, of whom there were only a few hundred at most, gathered in the city hall and elected their representatives. But in 1919, the Edén coalition government brought in universal suffrage in local elections, which (along with the aforementioned growth) meant that the body of voters ballooned to several thousand. To better serve these new voters, it was decided to split the city into two electoral wards, of which the southern one would still hold polls at the town hall, while the northern one would vote in the IOGT chapter hall. The split line was simple and understandable, following the high street through the city centre and then the highway west.

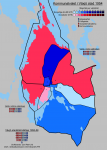

The growth continued, and in 1937 the time came to add a third ward, this time in the west of the city. Somewhere in between here, the city also switched from bloc vote to proportional representation, and aligned its election days with those for the county council, for which Växjö made up a constituency by itself as the only city in Kronoberg County. Despite universal suffrage, it remained a Conservative bastion for most of this period, and only as part of their nationwide landslide in 1938 did the Social Democrats manage to break through.

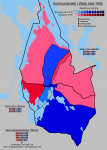

The Social Democrats, led by the energetic young councillor and former grammar school teacher Georg Lücklig, immediately decided to set about merging the two municipalities, in large part to secure the votes in Östregård, which was by now a heavily lower-middle-class suburb. Aided by the generally favourable attitude of Stockholm to urban boundary reform, they were able to get an order in council confirming this as early as autumn 1939, and on New Year's Day 1940, Växjö Rural Municipality and Östregård council both ceased to exist. As a result, Växjö again saw a big population increase, putting it over the 10,000 mark for the first time ever and requiring it to elect its council in two different constituencies rather than by citywide vote. To implement this, the city's wards were again redrawn, creating a north and a south constituency with equal populations (electing twenty councillors each) and a west and an east ward within each constituency. This was the division that would exist until 1949, when population growth again forced a rewarding, and the constituencies would exist until it was made possible to voluntarily abolish them in the early 60s, at which point Växjö immediately did so.