NOTE: Once again, lots of conjectural city boundaries on this. I may have been able to trace them properly, but to do so would've taken a

lot of time and effort, and I ultimately decided it wouldn't be worth it.

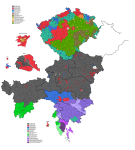

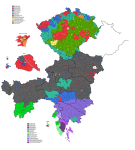

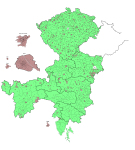

The Kingdom of Bohemia was the industrial heartland of the Empire. With some 6.3 million inhabitants, divided into 63 percent Czechs and 37 percent Germans (including Jews, of which Prague at least had quite a few), it was the second-most populated province of Austria, behind only Galicia, and since Galicia was overwhelmingly poor, rural and underdeveloped, Bohemia was the richest province, which under the 1906 electoral law meant it had the largest number of seats - 130 of them, divided into 75 Czech-majority seats and 55 German-majority seats. Quite helpfully, the Germans lived mainly along the outer edges of Bohemia, with even the towns outside the German-speaking region almost all being majority Czech, and this meant the districts could be quite easily drawn up without having to resort to extreme imbalances like what we saw in modern-day Slovenia. Of course, the towns and countryside were still separated, but the districts did tend to be fairly equal in population, with a few exceptions. Karlsbad, a rich spa town with only some 3,500 voters, got its own seat (district 88), while the Prague suburbs got lumped together in very awkward ways.

The party landscape in Bohemia, even among Germans, was quite different from that of "Austria proper". The language issue had flared up seriously in the 1890s after the ministry in Vienna proposed that Czech should be a co-official language within Bohemia, which caused an uproar among the German population because, while the Czechs could mostly speak German, very few German Bohemians knew any Czech, and this meant they would likely get sidelined for civil service jobs if the bilingual policy were implemented. This contributed to a general sense of German identity in Bohemia being under siege, hard as it might be to understand given their economic and political dominance up to that point, and that in turn meant that clerical politics found no real home among German Bohemians. Instead, with the exception of the mining regions of the Ore Mountains along the Saxon border, German Bohemia was dominated electorally by the German nationalist bloc. It was in large part thanks to Bohemia, Moravia and Austrian Silesia (which will come later) that the German nationalists were able to establish themselves as the largest bloc in the chamber overall in 1911.

The Czechs, meanwhile, voted largely along class or identity lines. The

Czech Clericals (gold-brown), a bloc comprised of the Catholic National-Conservative Party and the Czech Christian Social Party, did not do very well outside a specific region in eastern Bohemia in 1907, and disappeared entirely in 1911, while the

Old Czechs (gold), the standard-bearers of Czech nationalism going back to 1848, were only able to win a handful of seats in 1907 and only one in 1911. Instead, three major parties established themselves in 1907. First in votes, though not in seats, were the

Social Democrats, who (as mentioned) were somewhat separate from their German-Austrian counterparts - in 1911, all but one Czech deputy would split off altogether and create a new Autonomist Social Democratic Party, which I haven't depicted on the map because TOO MANY COLOURS. Second, and forming the largest group of deputies, was the

Czech Agrarian Party, which if you've been following

@Nanwe's Czechoslovak map series were the kernel of what would become the RSZML in Czechoslovakia. Of course, the "R" in that abbreviation stands for "Republican", so they couldn't very well call themselves that at this point. Third were the

Young Czechs, who split from the Old Czechs in the 1870s to protest them being insufficiently committed to the Czech national cause, and who attracted significant support from the established middle classes in urban parts of Bohemia. They were, however, increasingly being challenged for that role by the

Czech People's Socialist Party (orange - again, the direct ancestor organisation of the ČSNS in Czechoslovakia), a new-ish party (founded in 1897) that combined radical but non-Marxist socialism with a Czech nationalism that incorporated elements of the Hussite tradition. In 1911, the ČSNS were nearly able to beat the Young Czechs into third place among the Czech seats.