- Location

- Das Böse ist immer und überall

- Pronouns

- he/him

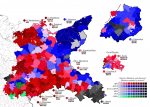

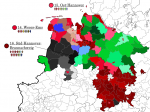

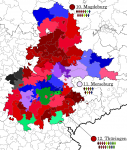

The WKV Sachsen-Thüringen (not to be confused with WKV Sachsen) included the Prussian province of Saxony as well as the states of Thüringen and Anhalt. This is another interesting one, as it's the first region we've looked at that's inside what I call the "Red Triangle" - the central region of Germany, bounded roughly by Hamburg, Frankfurt and Dresden, where the SPD tended to do especially well. This was certainly true of large areas within the WKV, with both the lignite fields around Halle, the small farms and manufacturing towns of the Thuringian Forest and the agricultural estates of the fertile Magdeburg Börde having provided reliable vote banks for the SPD before the war. In the Weimar Republic, however, the KPD provided strong competition in certain regions, particularly the lignite region. The Merseburg constituency actually returned a narrow plurality for the Communists, although in both 1924 elections, vote-splitting on the left had made the DNVP the strongest party. Magdeburg, for its part, was (like several other mid-sized Prussian cities) fairly good for the DVP, although the SPD were very far ahead of them.

Thüringen, meanwhile, was Interesting (TM). The state of Thüringen (which was smaller than the constituency) saw some of the most closely-fought state elections in the Weimar era, being both a stronghold of the old USPD and the first place where the Nazis got a foothold in state-level government (although that was still in the future in 1928). Compared to the Prussian part of the WKV, the DNVP was notably weak in Thüringen, and the right-wing camp tended to be headed up by the Thüringer Landbund, a highly conservative, nationalist, at times heavily anti-Semitic (but I repeat myself) agrarian party, which would be responsible for bringing the Nazis in from the cold in 1930. For the 1928 Reichstag elections, they participated in the Reichswahlvorschlag of the Christlich-Nationale Bauern- und Landvolkpartei (CNBL), which the English Wikipedia falsely claims only emerged after this election - in fact, while it would grow after it, it came about as an alliance of right-wing agrarian movements specifically to contest it, but did grow significantly due to DNVP defections afterwards, as Alfred Hugenberg consolidated his controversial leadership of the party and expelled elements opposed to his openly völkisch, conspiratorial nationalist outlook.

And then, of course, there was the Eichsfeld, the northwest corner of Thüringen, which had been part of the Archbishopric of Mainz and remained heavily Catholic as a result. This made the Centre Party significantly stronger in Thüringen than it would've been otherwise, and ensured they received a seat on the WKV level.

Yet another style note - Sachsen-Thüringen being the first WKV we've done that didn't face any of Germany's outer borders means I had to move the constituency names and overviews so as not to make the map pointlessly huge. Hopefully it works this way.

Thüringen, meanwhile, was Interesting (TM). The state of Thüringen (which was smaller than the constituency) saw some of the most closely-fought state elections in the Weimar era, being both a stronghold of the old USPD and the first place where the Nazis got a foothold in state-level government (although that was still in the future in 1928). Compared to the Prussian part of the WKV, the DNVP was notably weak in Thüringen, and the right-wing camp tended to be headed up by the Thüringer Landbund, a highly conservative, nationalist, at times heavily anti-Semitic (but I repeat myself) agrarian party, which would be responsible for bringing the Nazis in from the cold in 1930. For the 1928 Reichstag elections, they participated in the Reichswahlvorschlag of the Christlich-Nationale Bauern- und Landvolkpartei (CNBL), which the English Wikipedia falsely claims only emerged after this election - in fact, while it would grow after it, it came about as an alliance of right-wing agrarian movements specifically to contest it, but did grow significantly due to DNVP defections afterwards, as Alfred Hugenberg consolidated his controversial leadership of the party and expelled elements opposed to his openly völkisch, conspiratorial nationalist outlook.

And then, of course, there was the Eichsfeld, the northwest corner of Thüringen, which had been part of the Archbishopric of Mainz and remained heavily Catholic as a result. This made the Centre Party significantly stronger in Thüringen than it would've been otherwise, and ensured they received a seat on the WKV level.

Yet another style note - Sachsen-Thüringen being the first WKV we've done that didn't face any of Germany's outer borders means I had to move the constituency names and overviews so as not to make the map pointlessly huge. Hopefully it works this way.