NZ 1925/1928

- Location

- Das Böse ist immer und überall

- Pronouns

- he/him

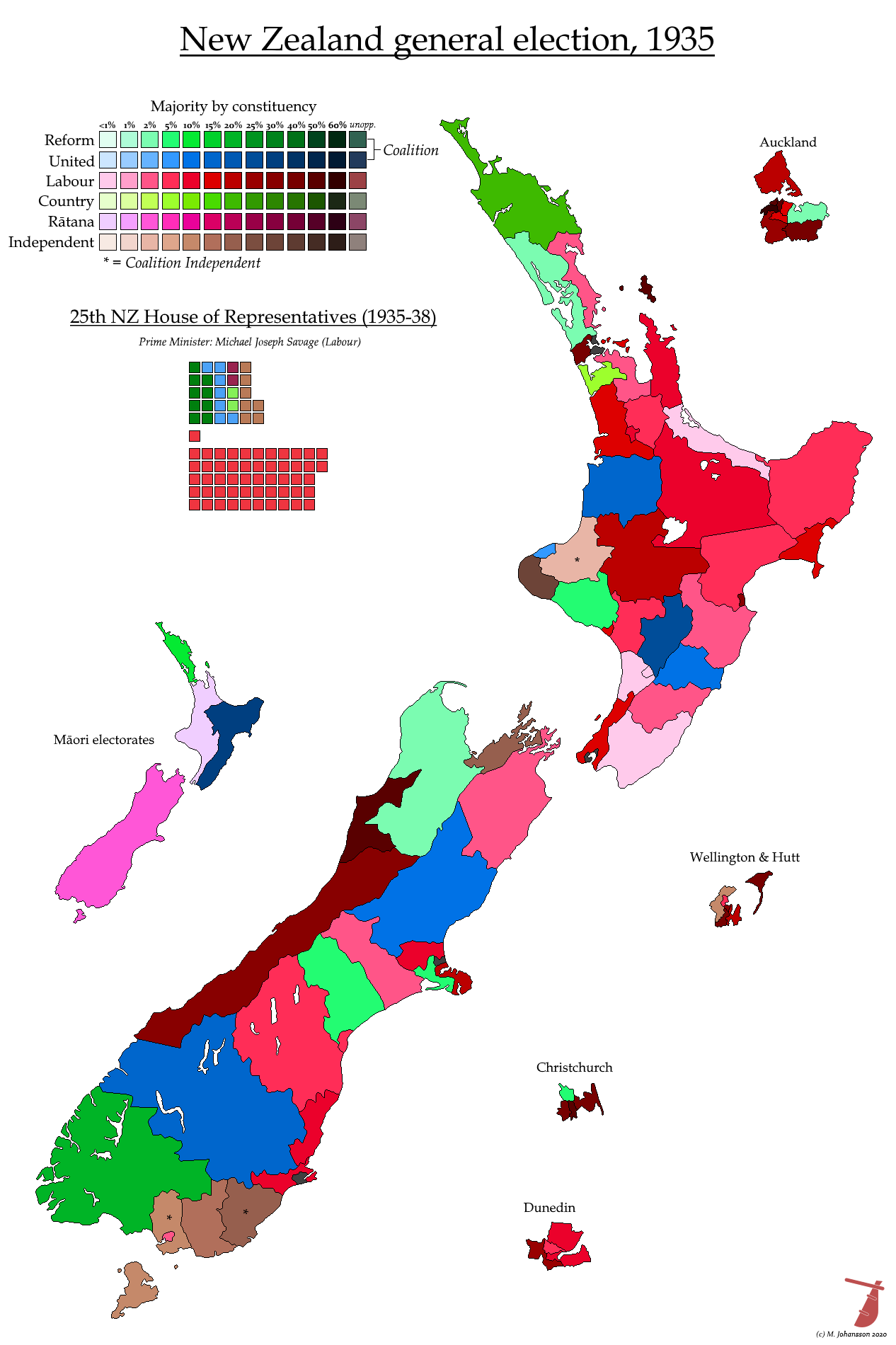

More NZ, and thanks again to @Uhura's Mazda for the writeups.

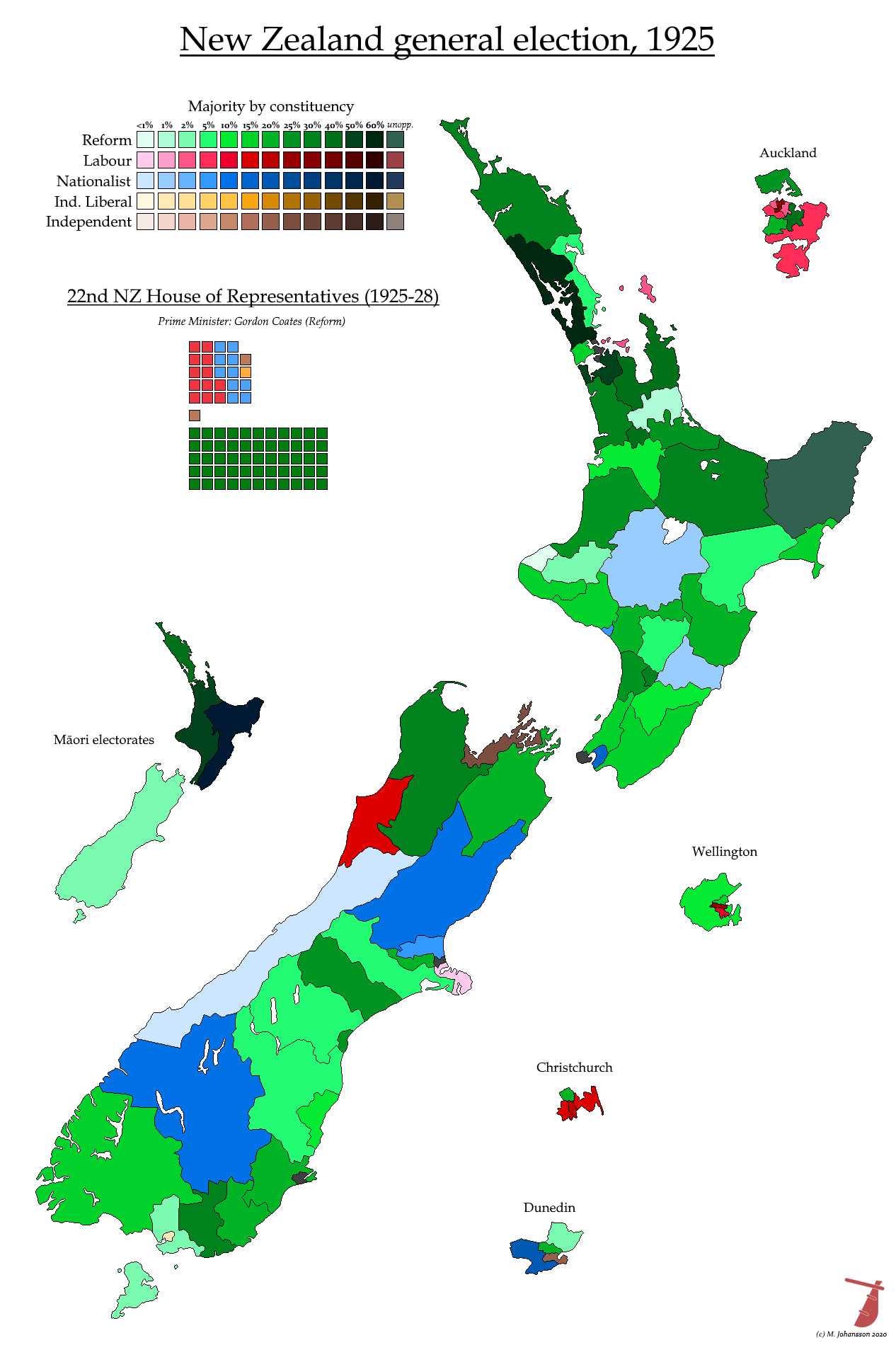

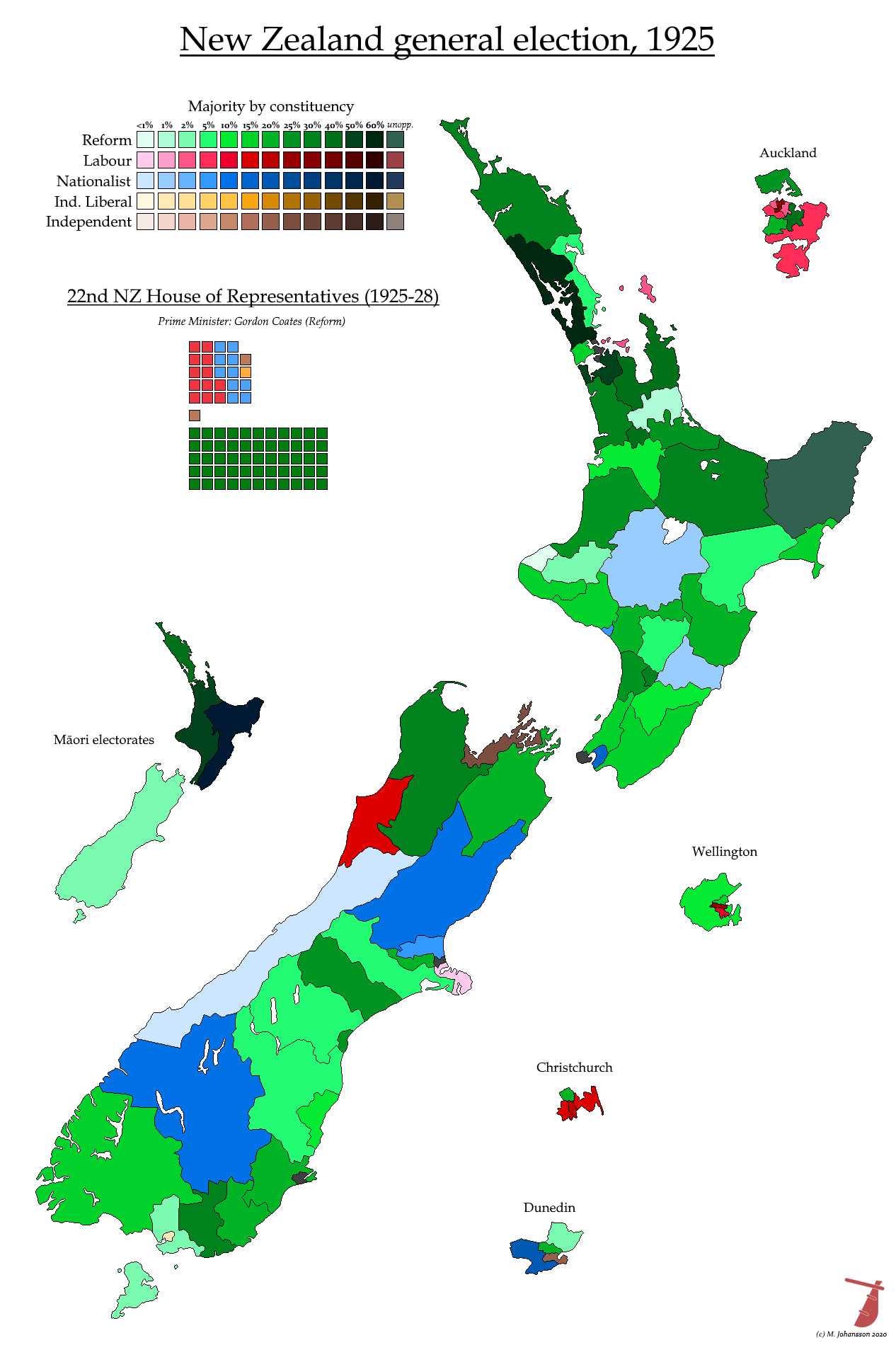

1925

1922 proved to be Farmer Bill Massey's last, rather anaemic, hurrah. He was dependent on the support of the crossbench and the two Liberals he'd won over, both of whom were rewarded for the treason with seats in the upper house and succeeded in their electorates by official Reformers. Massey became ill and retreated from public life in 1924 before dying early in the election year of 1925. Despite only winning a single majority at the polls, his time in office was second only to Richard Seddon's. Another similarity with Seddon - and with Ballance - was that he died in office while at least one potential successor was unready to participate in the battle for succession. To hold the fort, the elder statesman Sir Francis Bell stepped in on an interim basis to become simultaneously New Zealand's last Prime Minister from the upper house and its first Prime Minister to be born in New Zealand.

There were two front-runners. The closest thing the Reform Party had to an intellectual or an economist (very much of the laissez-faire stripe) was William Downie Stewart, who had only entered the House in 1919. However, he had developed rheumatoid arthritis during his War service and was often to be seen in an invalid chair. At the time of Massey's death, he was on a boat back from America, where he had been seeking a cure, and he sent a telegram advising the Reform caucus that he would happily serve under whomever they chose. In the event, only a tiny group of people around William Nosworthy disrupted the coronation of Gordon Coates.

Coates is an archetypal Kiwi PM - and like Bell, he was born in the country. He was brought up on a farm in Northland where he had learned to keep a bluff distance and a stiff upper lip. His lip was indeed rather stiff due to a childhood facial injury, and he grew a no-nonsense moustache to hide the disfigurement. Coates didn't know much about political theory, unlike Downie Stewart, but he had developed the reputation of a businesslike straight-shooter who didn't over-promise. This was clearly a resilient brand, as it grew despite the fact that he had shifted from being an Independent Liberal to putting Massey in power during his first few months as an MP.

Shortly afterwards, the Liberals also swapped out their leader. Thomas Wilford took the opportunity inherent in the death of the intransigent Massey to propose anew the idea of a 'fusion' between the non-Labour parties. For the first time, a working group of party bigwigs was set up, but it foundered upon the issue of a pre-election alliance, and it is unlikely that Coates was genuinely interested in the option. Wilford resigned in a fit of exasperation and was replaced by the stolid and unimaginative George Forbes. As a futile bid to argue the toss about the affair, the Liberals fought this election as the National Party, harking back to the wartime National Government, and fought the election on the basis of agreeing on virtually every policy with Reform and guilt-tripping them into fusion.

This strategy did not come off. As well as an unprepossessing leader, the Liberals also lacked policy strength and their advertising material was very poor compared to the Reformers'. Whereas Forbes was sold as "a plain man without frills", Reform's national organiser, Albert Davy, introduced populist, personalist slogans such as "With Coates and Confidence" and "Coats off with Coates". Reform's policy offer was just as vague as National's (just as Ward had promised a "legislative holiday" in his first election, Coates pledged "less political activity), which allowed Davy - an ardent free-marketeer who would shape New Zealand politics for the next decade - the leeway to use a third slogan, "More business in Government and less Government in business". This hollowed out the remnants of the urban Liberal business classes in favour of the traditional farmers' party, Reform.

Meanwhile, the Australian radical Harry Holland continued as Labour leader and marginally increased his party's vote. The main issue in Labour in these years was their original conviction that land ought to be nationalised - a policy which did not find favour among farmers, who had an emotional connection to freehold. A compromise position, influenced by the new MPs Frank Langstone (in Labour's first really rural electorate) and John A. Lee (who incidentally had been invited by Massey to join Reform), proposed a complicated of 'usehold' tenure, which was misinterpreted by Reform and Labour candidates alike. Langstone lost his seat and the whole party fell back by five seats to a total of 12, largely because of the flood of Liberal/National voters over to Reform.

The other seats went to the established Independents Statham and Atmore, who have been mentioned in previous installments. And in a blast from the past, former Prime Minister Sir Joseph Ward cut a deal with the local Liberal/National member to inherit the Invercargill electorate. He refused to fight the seat under any designation other than that of a Liberal, and was independent of the National caucus in the resultant House. The final minor force that must be mentioned is the Country Party, an electoral organisation belonging to the Auckland branch of the Farmers' Union, who had broke with Massey over the shortage of cheap credit with which to buy imported farming equipment. They performed pitifully against Coates in their first election.

The result of the election left Labour and National+Ward, equal on seat count, arguing over which of them should be the Official Opposition, in a contest reminiscent of two bald men fighting over a comb. The position remained in abeyance until the Eden by-election of the following June, which was triggered by the appointment of the incumbent as High Commissioner. Based on prosperous Auckland suburbs, it would normally have returned a Reformer, but - desperate to gain a first seat for women, 7 years after they were permitted to sit in the Parliament - Ellen Melville stood as an Independent Reform candidate and split the vote sufficiently to allow Labour to elect their first University-educated parliamentarian, Rex Mason. Not for the first time, a woman had caused trouble in Eden.

1925 was Reform's only landslide victory, fourteen years into their Government - and it proved to be too good to last.

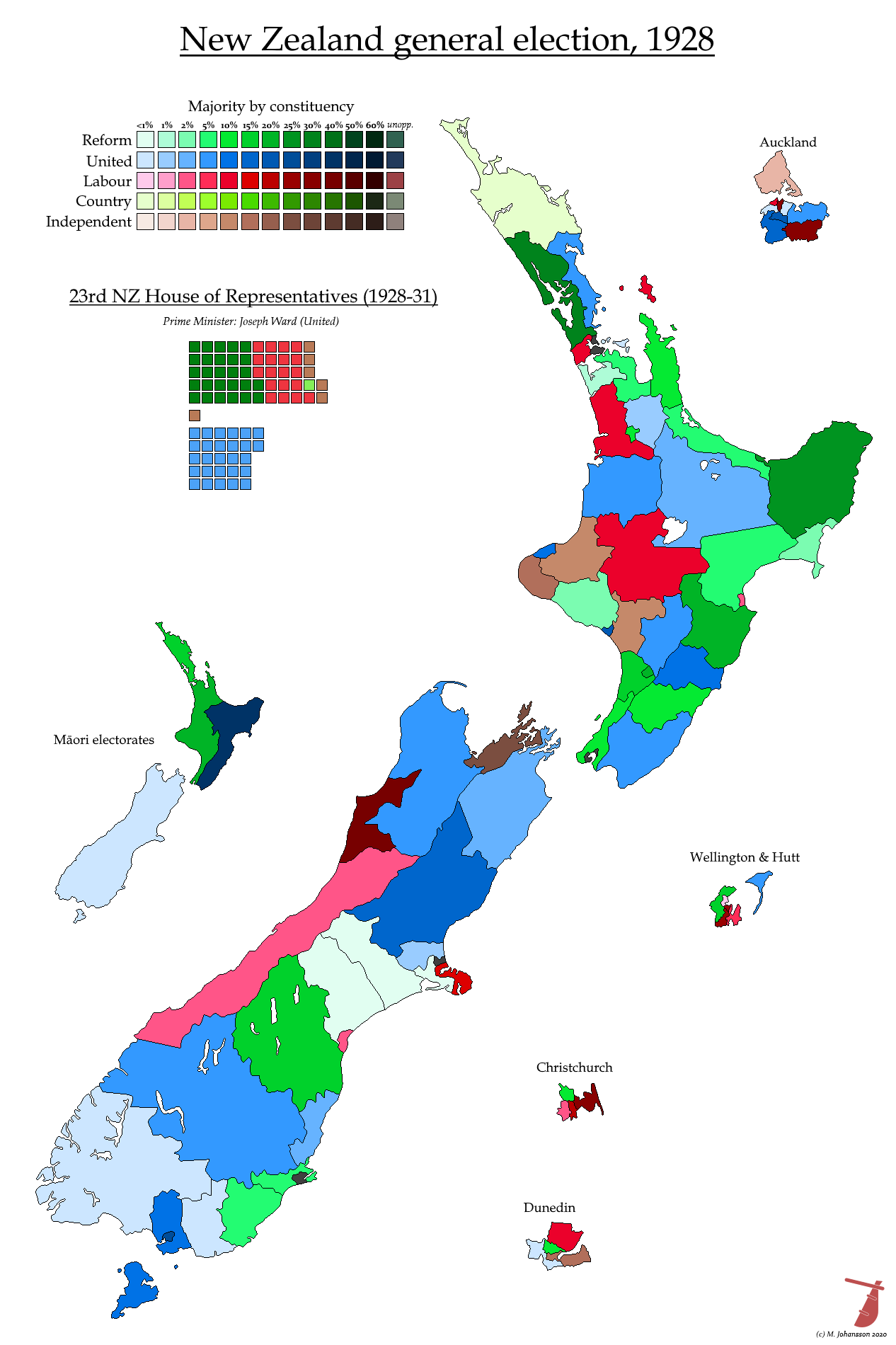

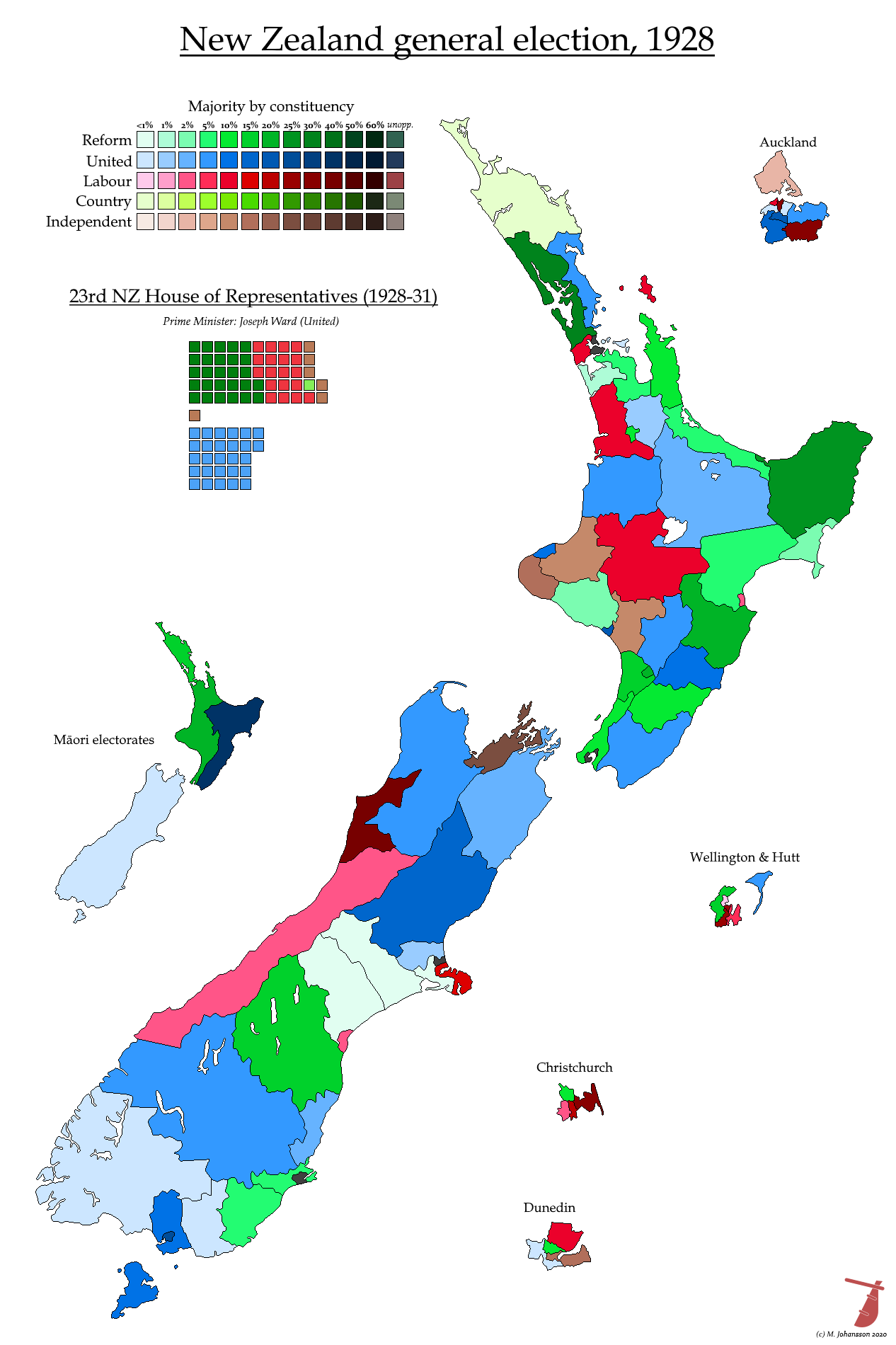

1928

Gordon Coates was not destined to be a long-serving Prime Minister, despite winning a vast majority in 1925. His personal failings included a shortage of well-developed ideas of his own and a concomitant willingness to be led by others. Around him gathered a 'think tank' of more intellectual people, principal among them being Bill Sutch, who saw New Zealand's trajectory as being towards state socialism. Sutch had some influence over Coates' policies, and was much later charged with spying for the Soviet Union - although this seems to have been a case of over-zealousness on the part of the SIS.

Back to the final stages of the Reform Government. Coates had finally won over the urban business community, especially in Auckland, by making positive noises about "less Government in business". In fact, he pursued quite the opposite course, principally by extending state control over the marketing of farming exports, but also by instituting a Family Allowance which was decried by the thrifty bourgeoisie as a dole, which was self-evidently a bad thing. To compound it all, it was obvious that Coates wasn't even taking these steps out of personal conviction. He spoke to one adviser before telling the London market that dairy products would be sold at a price set by the state, but changed his mind that afternoon (in favour of the price being set by the Dairy Board) when a certain dairying industrialist named William Goodfellow phoned him up and persuaded him the other way.

Albert Davy, the Mephistopheles of New Zealand electoral organising in the inter-war period, rapidly lost patience with the man to whom he had delivered such a massive majority. He founded a United New Zealand Political Organisation in 1927 which was bankrolled by the Auckland business community through William Goodfellow, who was equally sick of Coates. The Davy-Goodfellow group announced that it was happy to work with the remnants of the Liberal Party, who were now without an obvious leader or an obvious political niche. In 1925 they had run on platitudes and an intention to merge with Reform, none of which dissuaded them from accusing the equally vacuous and pro-Reform Reform Party of stealing their policies. Now the dull George Forbes was officially leader of the National Party, but there was another group following Bill Veitch. Veitch had first been elected for Wanganui as one of the first Independent Labour MPs but was since long-wedded to the Liberals after breaking with Labour over his support for conscription during the Great War - and now he was stumping the country preaching a rejuvenation of liberalism. Forbes was so weak that he pretended that Veitch was doing this with his blessing.

A final remnant of the Liberal Party was the aging figure of Sir Joseph Ward, Prime Minister from 1906 to 1912, who now bore sole rights to the Liberal name. In 1928, everything flowed the right way for both Ward and for Albert Davy, who pulled Ward, Forbes and Veitch into his own organisation to form the United Party. United didn't have the most auspicious of starts. The first conference saw a hotly contested leadership ballot between George Forbes and Alfred Ransom (whose only real political quality was that he'd been around for a few years) in which Ransom edged out the incumbent. However, the vote was subject to some irregularities and, in a rerun, the conference decided to avoid contention and drafted Ward unanimously.

Ward was now a shadow of his former self, and looking very thin and wan compared to his glory days. He was also suffering from intermittent diabetic blackouts and becoming a little senile. The omens didn't look good for the new party, based on has-beens, opportunists and uncompromising devotees of laissez-faire economics. But this all changed at the launch of the United Party's campaign. At the point that Ward had been supposed to promise to borrow only the paltry sum of £7 million in the term, he had a spell of blindness and had to continue his speech from memory - he pledged to borrow £70 million a year, and the crowd went wild. Ever the canny operator, Davy ensured that this commitment was picked up by the newspapers, and the Uniteds had to suddenly drop their previously claimed principles in search of the support of the electorate.

Meanwhile, the early flutterings of the Great Depression were being felt, and unemployment hit record levels in 1927, and then again in 1928. Conditions were perfect for Labour to progress, aided by the fact that Harry Holland had kicked the whole land reform debate into touch by replacing long, involved explanations of nationalisation or usehold tenure with a simple sentence about "closer settlement". Although Labour reached a quarter of the vote and its best result so far in terms of seats, they were disappointed by the fact that United had appealed to their voters by promising much greater state spending.

Two minor parties emerged in 1928 election: the Country Party of disaffected farmers in the north of the North Auckland managed to capitalise on Reform's unpopularity by electing Captain Harold Rushworth in the Bay of Islands - which, as an electorate, was rarely swayed by loyalty to major parties. Rushworth's margin was just two votes, and the Reformer incumbent, Allen Bell, alleged voting irregularities which precipitated a voiding of the result and a by-election, in which Rushworth increased his majority in a straight fight. An even closer vote was seen in the Southern Maori electorate, where Eruera Tirikatene of the Ratana movement tied with the United candidate and lost on the casting vote of the returning officer. Ratana was the political vehicle attached to Maori religious revivalist group which wished to get the Treaty of Waitangi re-established in the law of the land.

At the close of the polls, Reform was the only party to reach a third of the vote, but United and United-aligned Independents had slightly more seats. Both United and Labour voted no confidence in Coates (previously, the Liberals had tended to get cold feet before voting for no-confidence motions they themselves had proposed, if they got a whiff that Labour were going to vote with them). Now, the only realistic Government was a minority United ministry, led by the political Lazarus, Joseph Ward, and propped up by Labour. The influx of new United members was both a blessing and a problem: as very few of them had any experience in the House, some were sworn in as Ministers on their first day in the job, while the Independent Harry Atmore was drafted in as Minister of Education.

It was this motley Government that would face the deepening challenge of the Depression.

1925

1922 proved to be Farmer Bill Massey's last, rather anaemic, hurrah. He was dependent on the support of the crossbench and the two Liberals he'd won over, both of whom were rewarded for the treason with seats in the upper house and succeeded in their electorates by official Reformers. Massey became ill and retreated from public life in 1924 before dying early in the election year of 1925. Despite only winning a single majority at the polls, his time in office was second only to Richard Seddon's. Another similarity with Seddon - and with Ballance - was that he died in office while at least one potential successor was unready to participate in the battle for succession. To hold the fort, the elder statesman Sir Francis Bell stepped in on an interim basis to become simultaneously New Zealand's last Prime Minister from the upper house and its first Prime Minister to be born in New Zealand.

There were two front-runners. The closest thing the Reform Party had to an intellectual or an economist (very much of the laissez-faire stripe) was William Downie Stewart, who had only entered the House in 1919. However, he had developed rheumatoid arthritis during his War service and was often to be seen in an invalid chair. At the time of Massey's death, he was on a boat back from America, where he had been seeking a cure, and he sent a telegram advising the Reform caucus that he would happily serve under whomever they chose. In the event, only a tiny group of people around William Nosworthy disrupted the coronation of Gordon Coates.

Coates is an archetypal Kiwi PM - and like Bell, he was born in the country. He was brought up on a farm in Northland where he had learned to keep a bluff distance and a stiff upper lip. His lip was indeed rather stiff due to a childhood facial injury, and he grew a no-nonsense moustache to hide the disfigurement. Coates didn't know much about political theory, unlike Downie Stewart, but he had developed the reputation of a businesslike straight-shooter who didn't over-promise. This was clearly a resilient brand, as it grew despite the fact that he had shifted from being an Independent Liberal to putting Massey in power during his first few months as an MP.

Shortly afterwards, the Liberals also swapped out their leader. Thomas Wilford took the opportunity inherent in the death of the intransigent Massey to propose anew the idea of a 'fusion' between the non-Labour parties. For the first time, a working group of party bigwigs was set up, but it foundered upon the issue of a pre-election alliance, and it is unlikely that Coates was genuinely interested in the option. Wilford resigned in a fit of exasperation and was replaced by the stolid and unimaginative George Forbes. As a futile bid to argue the toss about the affair, the Liberals fought this election as the National Party, harking back to the wartime National Government, and fought the election on the basis of agreeing on virtually every policy with Reform and guilt-tripping them into fusion.

This strategy did not come off. As well as an unprepossessing leader, the Liberals also lacked policy strength and their advertising material was very poor compared to the Reformers'. Whereas Forbes was sold as "a plain man without frills", Reform's national organiser, Albert Davy, introduced populist, personalist slogans such as "With Coates and Confidence" and "Coats off with Coates". Reform's policy offer was just as vague as National's (just as Ward had promised a "legislative holiday" in his first election, Coates pledged "less political activity), which allowed Davy - an ardent free-marketeer who would shape New Zealand politics for the next decade - the leeway to use a third slogan, "More business in Government and less Government in business". This hollowed out the remnants of the urban Liberal business classes in favour of the traditional farmers' party, Reform.

Meanwhile, the Australian radical Harry Holland continued as Labour leader and marginally increased his party's vote. The main issue in Labour in these years was their original conviction that land ought to be nationalised - a policy which did not find favour among farmers, who had an emotional connection to freehold. A compromise position, influenced by the new MPs Frank Langstone (in Labour's first really rural electorate) and John A. Lee (who incidentally had been invited by Massey to join Reform), proposed a complicated of 'usehold' tenure, which was misinterpreted by Reform and Labour candidates alike. Langstone lost his seat and the whole party fell back by five seats to a total of 12, largely because of the flood of Liberal/National voters over to Reform.

The other seats went to the established Independents Statham and Atmore, who have been mentioned in previous installments. And in a blast from the past, former Prime Minister Sir Joseph Ward cut a deal with the local Liberal/National member to inherit the Invercargill electorate. He refused to fight the seat under any designation other than that of a Liberal, and was independent of the National caucus in the resultant House. The final minor force that must be mentioned is the Country Party, an electoral organisation belonging to the Auckland branch of the Farmers' Union, who had broke with Massey over the shortage of cheap credit with which to buy imported farming equipment. They performed pitifully against Coates in their first election.

The result of the election left Labour and National+Ward, equal on seat count, arguing over which of them should be the Official Opposition, in a contest reminiscent of two bald men fighting over a comb. The position remained in abeyance until the Eden by-election of the following June, which was triggered by the appointment of the incumbent as High Commissioner. Based on prosperous Auckland suburbs, it would normally have returned a Reformer, but - desperate to gain a first seat for women, 7 years after they were permitted to sit in the Parliament - Ellen Melville stood as an Independent Reform candidate and split the vote sufficiently to allow Labour to elect their first University-educated parliamentarian, Rex Mason. Not for the first time, a woman had caused trouble in Eden.

1925 was Reform's only landslide victory, fourteen years into their Government - and it proved to be too good to last.

1928

Gordon Coates was not destined to be a long-serving Prime Minister, despite winning a vast majority in 1925. His personal failings included a shortage of well-developed ideas of his own and a concomitant willingness to be led by others. Around him gathered a 'think tank' of more intellectual people, principal among them being Bill Sutch, who saw New Zealand's trajectory as being towards state socialism. Sutch had some influence over Coates' policies, and was much later charged with spying for the Soviet Union - although this seems to have been a case of over-zealousness on the part of the SIS.

Back to the final stages of the Reform Government. Coates had finally won over the urban business community, especially in Auckland, by making positive noises about "less Government in business". In fact, he pursued quite the opposite course, principally by extending state control over the marketing of farming exports, but also by instituting a Family Allowance which was decried by the thrifty bourgeoisie as a dole, which was self-evidently a bad thing. To compound it all, it was obvious that Coates wasn't even taking these steps out of personal conviction. He spoke to one adviser before telling the London market that dairy products would be sold at a price set by the state, but changed his mind that afternoon (in favour of the price being set by the Dairy Board) when a certain dairying industrialist named William Goodfellow phoned him up and persuaded him the other way.

Albert Davy, the Mephistopheles of New Zealand electoral organising in the inter-war period, rapidly lost patience with the man to whom he had delivered such a massive majority. He founded a United New Zealand Political Organisation in 1927 which was bankrolled by the Auckland business community through William Goodfellow, who was equally sick of Coates. The Davy-Goodfellow group announced that it was happy to work with the remnants of the Liberal Party, who were now without an obvious leader or an obvious political niche. In 1925 they had run on platitudes and an intention to merge with Reform, none of which dissuaded them from accusing the equally vacuous and pro-Reform Reform Party of stealing their policies. Now the dull George Forbes was officially leader of the National Party, but there was another group following Bill Veitch. Veitch had first been elected for Wanganui as one of the first Independent Labour MPs but was since long-wedded to the Liberals after breaking with Labour over his support for conscription during the Great War - and now he was stumping the country preaching a rejuvenation of liberalism. Forbes was so weak that he pretended that Veitch was doing this with his blessing.

A final remnant of the Liberal Party was the aging figure of Sir Joseph Ward, Prime Minister from 1906 to 1912, who now bore sole rights to the Liberal name. In 1928, everything flowed the right way for both Ward and for Albert Davy, who pulled Ward, Forbes and Veitch into his own organisation to form the United Party. United didn't have the most auspicious of starts. The first conference saw a hotly contested leadership ballot between George Forbes and Alfred Ransom (whose only real political quality was that he'd been around for a few years) in which Ransom edged out the incumbent. However, the vote was subject to some irregularities and, in a rerun, the conference decided to avoid contention and drafted Ward unanimously.

Ward was now a shadow of his former self, and looking very thin and wan compared to his glory days. He was also suffering from intermittent diabetic blackouts and becoming a little senile. The omens didn't look good for the new party, based on has-beens, opportunists and uncompromising devotees of laissez-faire economics. But this all changed at the launch of the United Party's campaign. At the point that Ward had been supposed to promise to borrow only the paltry sum of £7 million in the term, he had a spell of blindness and had to continue his speech from memory - he pledged to borrow £70 million a year, and the crowd went wild. Ever the canny operator, Davy ensured that this commitment was picked up by the newspapers, and the Uniteds had to suddenly drop their previously claimed principles in search of the support of the electorate.

Meanwhile, the early flutterings of the Great Depression were being felt, and unemployment hit record levels in 1927, and then again in 1928. Conditions were perfect for Labour to progress, aided by the fact that Harry Holland had kicked the whole land reform debate into touch by replacing long, involved explanations of nationalisation or usehold tenure with a simple sentence about "closer settlement". Although Labour reached a quarter of the vote and its best result so far in terms of seats, they were disappointed by the fact that United had appealed to their voters by promising much greater state spending.

Two minor parties emerged in 1928 election: the Country Party of disaffected farmers in the north of the North Auckland managed to capitalise on Reform's unpopularity by electing Captain Harold Rushworth in the Bay of Islands - which, as an electorate, was rarely swayed by loyalty to major parties. Rushworth's margin was just two votes, and the Reformer incumbent, Allen Bell, alleged voting irregularities which precipitated a voiding of the result and a by-election, in which Rushworth increased his majority in a straight fight. An even closer vote was seen in the Southern Maori electorate, where Eruera Tirikatene of the Ratana movement tied with the United candidate and lost on the casting vote of the returning officer. Ratana was the political vehicle attached to Maori religious revivalist group which wished to get the Treaty of Waitangi re-established in the law of the land.

At the close of the polls, Reform was the only party to reach a third of the vote, but United and United-aligned Independents had slightly more seats. Both United and Labour voted no confidence in Coates (previously, the Liberals had tended to get cold feet before voting for no-confidence motions they themselves had proposed, if they got a whiff that Labour were going to vote with them). Now, the only realistic Government was a minority United ministry, led by the political Lazarus, Joseph Ward, and propped up by Labour. The influx of new United members was both a blessing and a problem: as very few of them had any experience in the House, some were sworn in as Ministers on their first day in the job, while the Independent Harry Atmore was drafted in as Minister of Education.

It was this motley Government that would face the deepening challenge of the Depression.