- Location

- Tamaki Makaurau

The Radical Social Liberal Party is one of Britain's more unique political institutions, originally founded as a non-partisan movement in the late 1940s by a group of servicemen returned from the occupation of West Germany, where they had been influenced by a small German party of the same name. The RSLP, from its inception, has promoted as its core tenets the three prongs of Freiwirtschaft - an economic policy invented by the German-Argentinean Silvio Gesell. Gesell believed in free trade (the RSLP's most mainstream idea), free land (i.e. communal ownership of land), and free money (i.e. the discouragement of money-hoarding by charging a demurrage tax on unspent currency). These ideas have been the basis of RSLP policy ever since.

Originally known as the Radical Social Liberal Movement, the group infiltrated the Liberal Party in one of its weaker historic phases, while publishing a vast quantity of pamphlets under its own auspices (David Hoggard has an almost-complete collection in his Political Ephemera Archive above the Izmir Kebab shop in Gainsborough, if you're interested). However, the link with the Liberals eventually came to an end in the late 1960s when the Party grew uncomfortable about joint projects with the Gesellschaft think-tank in Germany, which employed more ex-fascists than was deemed acceptable. The Radical Social Liberals, long since seen as "cranks" even by the oddballs who made up the supermajority of the Liberal membership in those days, were expelled in the dramatic 1969 Conference, which is still commemorated in song at the Lib Dem Glee Club.

The currency cranks founded an independent party in the aftermath of the rupture, and became a tabloid favourite: disreputable publications painted their Free Economics Courses as sessions for indoctrination and brainwashing, when in fact cultism proper was limited to a few splinters. The slavery case associated with the Institute of Free Economic Thought reflected negatively on the main stream of the movement due to media hostility, much to the concern of those who had thrust the culprits out of the Party as early as 1972.

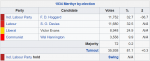

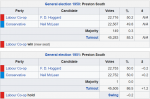

Electoral victories eluded the RSLP in the early years, apart from some local election gains in areas of heavy organisation, such as Bradford. Fortunately for the Party, the UK implemented Single Transferable Vote for the 1979 European elections. The electorate jumped towards minor parties (leaving the default protest option, the Liberals, with a disappointing poll), returning one MEP apiece from the Ecology, Communist and Radical Social Liberal Parties, as well as three from the National Front - who split three ways before the next election.

Subsequently, while the RSLP has only ever held one seat in Westminster (Bradford West after the 2012 by-election), it maintained a presence in Strasbourg until Britain left the European Union. The Party's promotion of Free Trade caused some internal division on the EEC question in the early years, but they have generally held to the idea that the EU is a force for backward-looking protectionism ever since they discovered that it paid electoral dividends. They were, therefore, the centrist wing of Farage's Independence Alliance from its formation until the post-Referendum collapse. As an independent party, in 2019, they claimed credit for unseating the last Official National Front MEP, which caused some confusion among pro-Europe anti-fascists - the ONF, of course, being very much in favour of the EU.

There are big questions about what the RSLP's future looks like without EU funding or parliamentary seats. But one thing is certain: these cranks will never stop talking about local currency schemes.

Originally known as the Radical Social Liberal Movement, the group infiltrated the Liberal Party in one of its weaker historic phases, while publishing a vast quantity of pamphlets under its own auspices (David Hoggard has an almost-complete collection in his Political Ephemera Archive above the Izmir Kebab shop in Gainsborough, if you're interested). However, the link with the Liberals eventually came to an end in the late 1960s when the Party grew uncomfortable about joint projects with the Gesellschaft think-tank in Germany, which employed more ex-fascists than was deemed acceptable. The Radical Social Liberals, long since seen as "cranks" even by the oddballs who made up the supermajority of the Liberal membership in those days, were expelled in the dramatic 1969 Conference, which is still commemorated in song at the Lib Dem Glee Club.

The currency cranks founded an independent party in the aftermath of the rupture, and became a tabloid favourite: disreputable publications painted their Free Economics Courses as sessions for indoctrination and brainwashing, when in fact cultism proper was limited to a few splinters. The slavery case associated with the Institute of Free Economic Thought reflected negatively on the main stream of the movement due to media hostility, much to the concern of those who had thrust the culprits out of the Party as early as 1972.

Electoral victories eluded the RSLP in the early years, apart from some local election gains in areas of heavy organisation, such as Bradford. Fortunately for the Party, the UK implemented Single Transferable Vote for the 1979 European elections. The electorate jumped towards minor parties (leaving the default protest option, the Liberals, with a disappointing poll), returning one MEP apiece from the Ecology, Communist and Radical Social Liberal Parties, as well as three from the National Front - who split three ways before the next election.

Subsequently, while the RSLP has only ever held one seat in Westminster (Bradford West after the 2012 by-election), it maintained a presence in Strasbourg until Britain left the European Union. The Party's promotion of Free Trade caused some internal division on the EEC question in the early years, but they have generally held to the idea that the EU is a force for backward-looking protectionism ever since they discovered that it paid electoral dividends. They were, therefore, the centrist wing of Farage's Independence Alliance from its formation until the post-Referendum collapse. As an independent party, in 2019, they claimed credit for unseating the last Official National Front MEP, which caused some confusion among pro-Europe anti-fascists - the ONF, of course, being very much in favour of the EU.

There are big questions about what the RSLP's future looks like without EU funding or parliamentary seats. But one thing is certain: these cranks will never stop talking about local currency schemes.