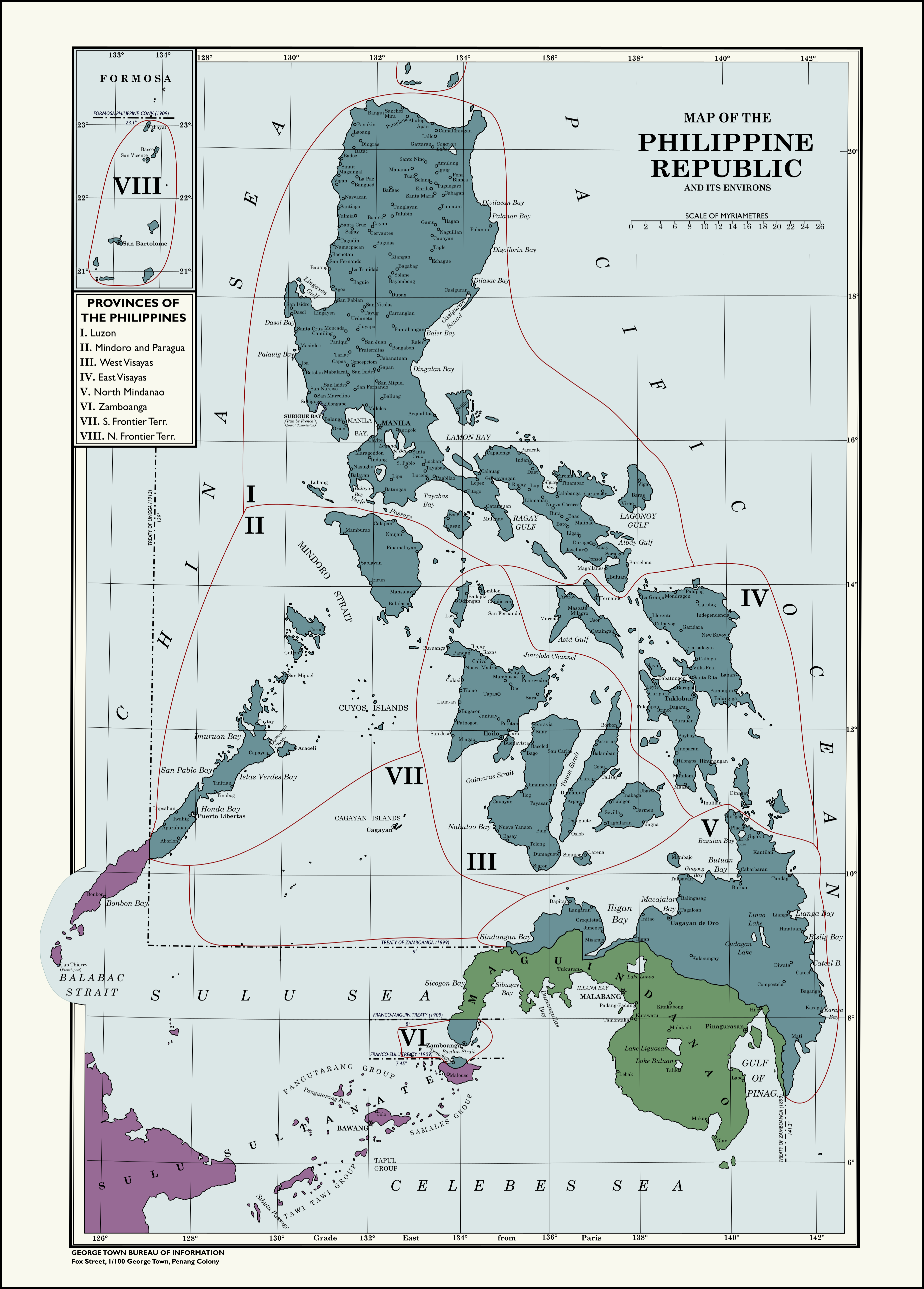

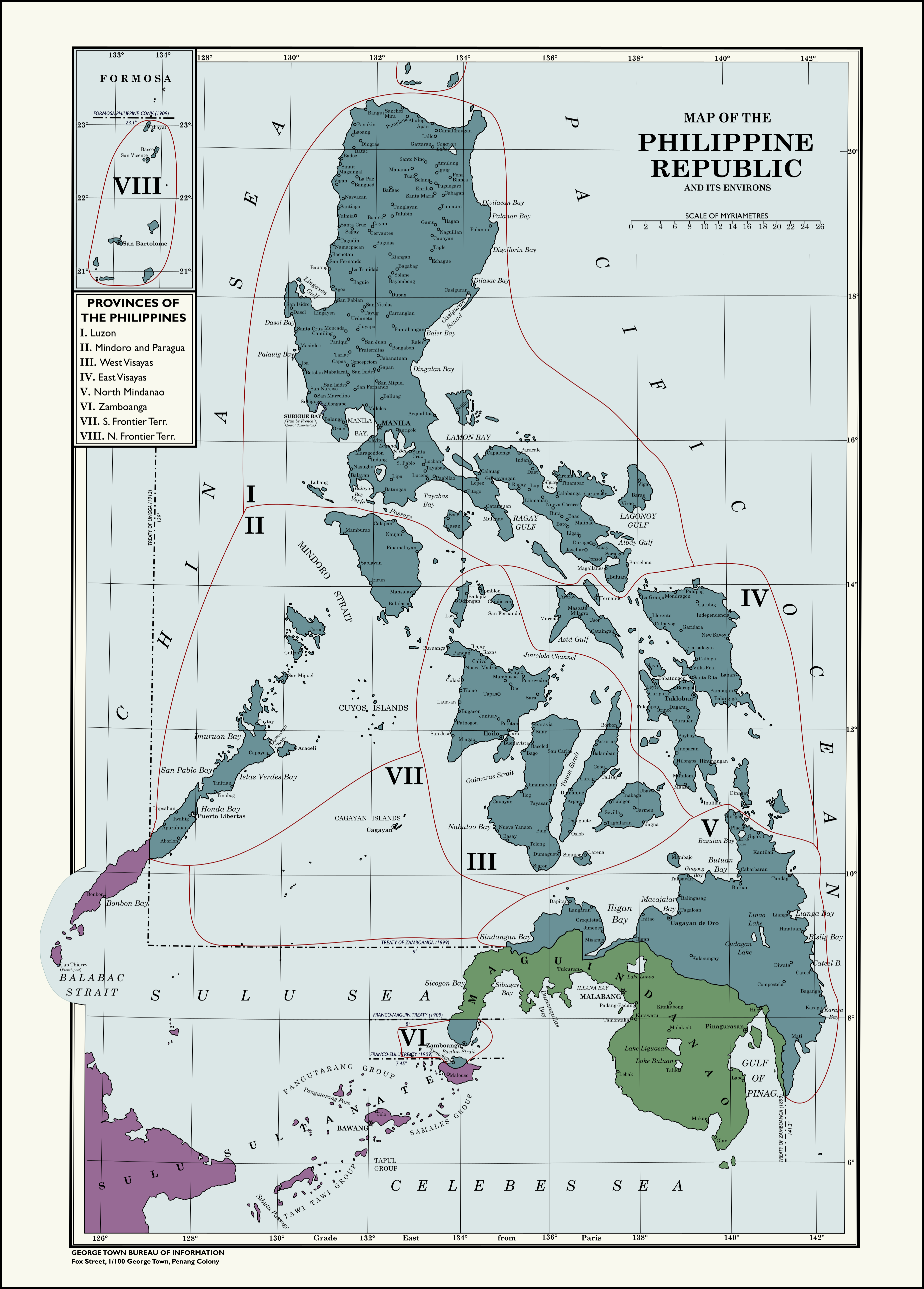

The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries proved to be periods of immense change for the Philippines. Long centred around the trade with China and the rest of East Asia, most famously the Manila Galleon between Manila and Acapulco, over the eighteenth century new crops were introduced to the isles, most particularly tobacco. This slowly turned the Spanish Philippines from a great trade entrepot into a resource colony in its own sake. Furthermore, Christianity in this period became entrenched as the faith of the Filipino people, as the older baybaylan faith came to an end with mass conversion, while Latin script became firmly entrenched as the script for the various Filipino languages. In 1762, a decisive moment came when the British took over Manila, as part of their warring with the Spanish during the Seven Years' War. Attempts by the British to gain local support entirely failed after Manila was brutally sacked, and Spanish forces quickly organized resistance in the name of the Catholic religion that successfully kept the British from expanding beyond the reach of their cannons in Manila. Furthermore, mass sepoy desertions sapped their strength. The result was that in the peace treaty Manila was traded away, and Spanish control resumed.

In its aftermath, the Spanish reorganized their colony, and they were quick to accuse the Chinese of supporting the British occupation, using this to justify persecution and new legal disabilities. This had numerous effects, most notably that the

mestizo descendants of Chinese and native unions found it better to consider themselves

indio, in contrast to elsewhere in Southeast Asia where they were more typically considered Chinese. At the same time, in the coming decades the Spanish further centred the Filipino economy around resource colonialism rather than just East Asia trade, granting a Basque company a monopoly for development in 1785. None of this, however, was enough to stop the arrival of an East India Company fleet to Manila in 1798 and the ensuing second British occupation. For the next eight years, Britain fought a long war against Spanish forces, and this time they proved more capable of occupying ports in the Visayas due to sheer numbers. However, at the same time, brutal British sacks sapped popularity immensely and attempts to gain local support floundered. Furthermore, Indian sepoys deserted in large numbers once again, caring little about this long war for masters they cared little about. And finally, after the end of the French Revolutionary Wars in 1804, by 1806 the last of the British troops left the Philippines.

Yet, over the course of this battle, the British greatly weakened Spanish grasp over the Philippines. The Spanish would face a number of local rebellions over the next few decades, and often Spanish rule did not simply resume but required defeating or conciliating local landowners or municipal councils. And at the same time, the first stirrings of Filipino nationalism came through over much of this. And more pertinently, the Spanish grasp over the economy was greatly weakened; farms were devastated, and export ports required reconstruction. This required a great deal of both skilled and unskilled labour, and the Spanish looked to China. Despite the Spanish again blaming the perfidious Chinese for supposedly supporting the British and launching a new round of persecution as a result, the need for the monies to flow outweighed this, and a great wave of Chinese migration to the Philippines arrived as a result. These new Chinese were often separate from older arrivals due to cultural divergence as well as that they often spoke Teochew rather than Hokkien. But they came nonetheless, and despite Spanish concerns over their "paganism" resulting in heavy-handed proselytization, they carved out a niche in trade, both internal and external, and as middlemen.

As most of them were men, this caused widespread intermarriage with locals, resulting in a new population of Chinese

mestizos that identified with

indios rather than the Chinese. Their interaction with the outside world meant they learned of ideas of liberalism and nationalism, often because the Spanish suppressed such ideas harshly. And so arose the so-called "Old Filipinos", the first generation of Filipino nationalism. They were centred around Manila but existed throughout the Spanish Philippines, and their goals were modest even as word of the independence of Venezuela electrified them. They wanted equality for all castes under the law, the opening of the friar orders to all the races, and some local government. But even this was too much for the Spanish authorities, and they were quick to crack down upon newspapers and political meetings, even while co-opting some of the new class. But nevertheless, a new civil society existed across the Philippines, a republic of letters that could only make the Spanish shudder.

This order was decisively interrupted with the eruption of war between Britain and Spain in 1848 over the New Granadine independence. Britain, despite being ruled by a new radical-liberal order, was now quick to use this as an excuse to launch some imperialism, and in 1851 a British fleet led by Lord Cochrane took over Manila. Learning from the brutal sacks which hampered the previous two occupations, Cochrane attempted to make this transition of power as orderly as possible, but it was insufficient in stopping the crimes bound to occur with imperial conquest. And the near-immediate British use of Manila as a trade entrepot for the pseudo-legal opium trade with China did not help matters. Attempting to salvage the situation, he attempted to gain local support by declaring the Philippines an "independent republic" with its flag a slightly adopted version of that of Venezuela. But this was, for the most part, viewed as a joke even by the liberals he intended to attract to his cause, and in this he wasn't helped by local tales of the first two British occupations as brutal events. And while the Spanish were far weaker relative to the British this time around, they quickly organized locals into regiments, even while ignoring the ideals spreading in them.

And from Mexico and Jabayi came a Spanish fleet, intent on retaking the Philippines. Meeting them first at Palanan Bay, Lord Cochrane made history - not in the good sense. Cochrane ordered a ship packed with sulphur, towed adjacent to the Spanish fleet, and burned; the effects of this were apparent when out came a poison gas directed by the wind, which forced the Spanish fleet into a frantic retreat from the gas of death. And though Cochrane attempted to ensure this would not harm civilians, the wind was a force he could not direct, and as it sent the sulphur gas to the land, it reached Palanan. Though dispersal kept it from being deadly or actively harmful, nevertheless the inhabitants of Palanan were forced to evacuate for days. Further attacks by the Spanish fleet were ones Cochrane had other innovations against, and through the use of cyanide shells he won a great number of battles through the terror of chemical warfare. But this was not enough to take over the entirety of the Philippines, and in treaty talks in 1854, Britain again traded it away for more immediate goals; the international criticism caused by Lord Cochrane birthing modern chemical warfare only made it less tenable.

In the next half-decade, the Filipino soldiers who gave their blood for the Spanish watched as, for all their pain, the Spanish changed administration little. Friars continued to be predominately-peninsular, legal equality failed to be achieved, and any constitutional government remained far-in-reach. This reached breaking point in 1860 when Filipino troops deposed the governor and declared General Juan Gerona, a notable veteran of the war, governor. After a period of legal limbo, finally the Spanish government and the Real Audiencia of Manila reluctantly accepted this experiment. And so, in this period, a truly Filipino government came to be. The press was freed, local councils and even an unofficial assembly of consultation were established, and far-reaching agrarian efficiency reforms were enacted. But this came at the great cost of Spanish colonial profits. Colonialism is a form of government that has always enriched the colonizer, and the Philippines established some small resemblance to self-rule reduced that. Finally, this reached a breaking point when, in 1868, the Real Audiencia of Manila arrested Governor Gerona and subjected him to a period of investigation. This investigation "revealed" various criminal offences, and after pondering the topic, in 1871, he was executed with the full approval of the king on these dubious charges. And this caused a massive army mutiny. The Philippine War of Independence had begun.

The various secret societies operating in and out of the army consolidated with these mutinies as the Young Philippines, and they quickly organized the various mutineers into the national army of the newly-declared Philippine Republic, with a new flag proudly displaying the

pa of Baybayin script as a symbol of Filipino separateness from Spain. In this period rebels successfully took over much of the western Visayas, as well as southern Luzon. Most notably, they took over Zamboanga. Yet, charges on Manila failed, and a takeover of Cavite in 1874 lasted eight days before a Spanish bombardment campaign unseated them. At the same time, the Pope being in exile in Madrid meant he was quick to excommunicate and issue papal bulls against any rebellions opposing the Spanish. But even as presidents-in-arms died in battle, and even as the Spanish prototyped new techniques of arresting entire villages and confining their inhabitants to camps, the Young Filipinos continued to fight, even as attempts to request various nations for assistance failed. But finally, by 1881, the Young Filipinos saw their treasuries drained, and in 1882 they signed a peace treaty with the Spanish in return for a new flow of money.

Moving to Formosa, technically a faraway province of the Qing exiled in Manchuria but in practice a French colony, the Young Filipinos successfully purchased new arms and got new training. Returning to the Philippines, they continued the Philippine War of Independence. But even this time, Manila remained free of their grasp. Finally, in 1886, requests for foreign intervention finally paid off when a French fleet entered Manila Bay; the French need to regain East Indies trade routes after the Dutch broke off their alliance made such intervention necessary. When word of this intervention came to Spain, fears of a land war with France led to an immediate informal agreement whereby Spain would evacuate the Philippines. However, it would not recognize the Philippines, the Pope continued to treat the new government as rebels, and the Spanish colony of Cochinchina hung over the new state like the sword of Damocles. But nevertheless, the Philippines formed one of the first modern democratic republics in Asia; the title of first modern democratic republic in Asia is fiercely contested between it, Punjab, and Goa, depending on definitions of "modern", "democratic", and "republic".

The new government was now intent on resolving these issues. It sought to relieve itself of the issue of a new Spanish conquest through recourse with France. According to a new agreement, France would be given a lease over Zamboanga and Subigue Bay for fifty years, and the Philippines was to be given old French ships and assurances of protection, in return for France diminishing the Spanish threat; this came when France successfully forced Spain to return Cochinchina to Viet Nam. But papal recognition did not come; instead, the Philippine government was forced to declare the formation of the Philippine Independent Catholic Church, with full custody of Catholic institutions in the nation. This tended to increase regional divides, as various regions and in particular the eastern Visayas did not sign on to this new church, as they had well-developed friar orders with some native enrollment. But quickly, this new church became the majority Filipino church; in practice, many did not even notice the change of church, especially as the change of the mass to the vernaculars and the rise of Positivist influence came later. But it very quickly linked up with Independent Catholic movements in Goa and Ceylon, and later to the Independent Catholic movement established following the codification of papal infallibility.

And so, with independence semi-secure, the new administrators of the nation, who formed what can only be described as an oligarchy, sought to reform the nation. In this, they were deeply affected by the ideology of Auguste Comte's positivism, which advocated the transformation of society towards a scientific system through a system marrying order and progress; some of Comte's sillier ideas, like the formation of a Catholic-style religion worshipping humanity rather than God, or a brand-new calendar rivaling the French Republican Calendar in terms of absurdity, were ones they tossed out without a moment of thought. The positivist oligarchy quickly created many new educational institutions on the model of French national schools, with the primary goal of educating engineers and scientists. Their architecture was cold and imposing and featured grand statues of scientific figures and above all Newton, with the intention of imposing upon the common citizen the power of science. New telegraph lines and railways were laid out and, with the later rise of photonics, wireless transmitters were constructed to connect islands like never before. But warning signs were there. To create all this impressive infrastructure, the government had to borrow money from the French, money they hoped to pay back in the future with their benefits. But the French had a different goal; they wanted to debt-trap the Philippines and turn it into a major artery of the new French colonial system in Southeast Asia. And as coal and gutta-percha from Aceh was imported and as Filipino merchants became commonplace in the ports of the other great French ally in Southeast Asia Johor, and as France effectively strongarmed the Philippines to give up its dreams of conquering the sultanates of Maguindanao and Sulu, it became clear that the Philippines was not quite free to choose its own destiny.

At the same time, the decline of the great generation of independence with the rise of the twentieth century saw a new one emerge. The oft-hostility of the Filipino government towards the Spanish government was not enough to outweigh the fact that, compared to Tagalog, the Spanish language put all the provinces at an equal disadvantage, but the new generation did not care; they believed only Tagalog should be the language of the nation. And this came with similar views towards the superiority of Tagalog culture. With the 1910s bringing them slowly to power, they put their plans into action. The Philippine Independent Catholic Church no longer gave mass in the language of the congregation; instead it was strictly in Tagalog. Tagalog now became a mandatory subject in schools across the nation; in addition to local language, yes, but it was a clear part of a trend. And Spanish was to be phased out of the nation entirely in 1925. These efforts continued to escalate, as language departments of universities were suppressed and Tagalog signage was made mandatory. Some even spoke of going further, of entirely replacing the Latin script with Baybayin, and to this end a new Act of the Cortes was passed making its instruction in school mandatory towards such a goal. This also came hand-in-hand with centralization efforts, to suppress the Visayan elite in particular. But this was all just too much.

Crisis came in 1924 when, with the Cry of Pampanga, a general declared his desire to reorganize the Philippines into a much more decentralized framework, and this came hand-in-hand with an all but expressed desire to strengthen regional elites and turn them into what were effectively feudal lords. He also advocated the primacy of Spanish and full recognition of regional languages so long as they met a percentage in their region. With that cry, he received support not only from Pampanga but from much of the Visayas - Negros was the chief exception - and with that the Philippine Civil War began. For a time it looked like this rebellion was going to be killed in its infancy, but then the French intercepted the Centralistas' fleet, destroying much of it. As a result, despite the Federalistas' dismal organization and the constant issues they faced due to their Visayan nationalist allies also plotting independence, they were buoyed by French support, and finally, by 1927, French troops bombarded Manila into surrendering. And so, with that, the Federalistas promulgated a new constitution which recognized the demands of the Cry of Pampanga, and they signed a convention with the Roman Catholic Church which allowed them to re-establish their hierarchy, with a far weaker position in the nation. Yet, at the same time, despite the general amnesty, Centralistas continued to exist and plot the restoration of their regime; with elections effectively coronations of the new landed elite, they only had the option of rebellion. This rebellion struck in 1930, and it was quickly repressed. But the Federalistas wondered how to suppress them.

In this period, the Philippines effectively became a French colony in all but the formal sense. The French leases of Zamboanga and Subic Bay were now for perpetuity. French conglomerates bought up much of Negros and other islands well known for production, and they brought Tamil workers from French India to work on them. With the Philippines facing rising and rising colossal debt it could not pay off, in 1931 it was forced to default and a French-appointed Public Debt Administration effectively became a third chamber of the Cortes. It turned independence into a joke, even as national institutions continued to exist. And the Centralistas saw all that was occurring, and they were more and more horrified. In 1932, they launched another rebellion, and though it too got crushed, the Federalistas was forced to ponder on better tactics to suppress them. After some talks in which the Centralistas requested democratization in a purely self-interested belief it could bring them back to power, the following year an Act of the Cortes established substantive tangible efforts towards democratization. And finally, in 1935, the presidential election brought the youthful Ramon del Fierro to power.

Born in Cebu to a poor background, he initially sought to enroll in the seminary but quit over a crisis of faith; with the knowledge he obtained from his education, he was able to enroll as an unusually old student in legal education, and from there he became a lawyer well-known for his wit. He remained distant from politics during the Philippine Civil War, but afterwards he became quickly very averse towards Federalista control of the nation and joined up with Centralistas. During the 1930 rebellion, although he refused to rebel, the private militia of a local aristocrat nevertheless stormed his house and killed his good friend. After this, del Fierro no longer felt safe in Cebu, and instead he chose to move to Manila. Escaping the 1932 rebellion by fleeing to the country, he was then involved in the negotiations for democratization, and finally in 1935 as a relative unknown uninvolved in the civil war, the Centralistas nominated him for president, and he surprisingly won.

In power, del Fierro initially continued existing policies; his most notable action was to add a new tax for a fund to pay off the Philippines' immense debt, instead of following the bad faith suggestions of the Public Debt Administration. Indeed, relieving the debt was his great mission. The unpopular tax greatly diminished his popularity. The Croatian War erupted in 1937 between France and Germany, over Croatia's unilateral declaration of independence; it was here that del Fierro truly shined when he negotiated directly with the French government with Paris via photonic transmission, rather than the government in Zamboanga, and finally, he achieved an offer with the war looking dire for the French. In return for a total relief of Philippine public debt and the return of Zamboanga, the existing monies of the debt relief fund would be sufficient in addition to the recruiting of Filipino soldiers on the side of the French. Furthermore, the French presence in Subigue Bay would be reduced to merely the naval base by 1960. This was agreed by both parties; both parties knew the French would be perfectly willing to betray it. But the war continued, and even as Filipinos died for the French, del Fierro strengthened Filipino control over its new territories, and he successfully incentivized various French landowners to sell off their land to Filipinos. He also unified provinces into larger, increasingly arbitrary units that allowed him to play regional oligarchies off of one another. And finally the Croatian War came to an end in 1941. Though del Fierro braced himself for a French intervention, it did not come, for France's desire to reclaim control over its pseudo-colony was now weakened. Furthermore, the discovery of rare earth elements in French New Guinea focused French colonialism with all its brutality there, rather than in the Philippines.

And thus, Ramon del Fierro spent the remainder of his presidency promulgating further reform. He broke up large estates and granted land to the landless. He opened new irrigation networks and created new dams for electricity generations. He famously declared, "Dams are the churches of the modern Philippines", and by doing so he summed up the sentiments of the era. He opened up new educational and medical institutions. But he could only do so much in his remaining years, for his two-term limit was to be hit in 1945. But he still had so much of his agenda to complete. And so, he attempted to revise term limits, and give himself one more term. When this amendment attempt was defeated in the Cortes, he attempted to make legal arguments to justify going around this; in one notably ridiculous argument, he claimed that re-election was a human right. But this was refused, and in 1945 he finally left office reluctantly and retired to his old home at Cebu, letting his successor lead the nation. His re-election attempt aside, he has a generally positive legacy.

And so, finally, the Philippines had a chance to plot its destiny itself.