- Location

- Das Böse ist immer und überall

- Pronouns

- he/him

Since we're apparently structuring this forum by author, this is where I'll go ahead and post my speed maps that I don't consider worthy to go on the DA, as well as any other graphical material I feel I have to put out.

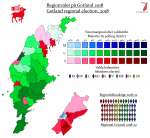

To begin with, the 1911 general election was the first in Sweden to be held by PR... or so we're told. In fact, the election law providing for universal male suffrage (nearly) and proportional representation was passed in 1909, and elections to the county councils were held under the system thus established in the spring of 1910. Well, they were held under the system established for local elections, which was a bit different.

Until this point, while the Second Chamber of the Riksdag had been elected by direct, equal suffrage for anyone who passed a tax threshold, municipal and county council elections had operated under weighted suffrage. Any legal person paying taxes to a municipality - whether a person, a company or an economic association - "owned" votes as a product of their taxation. The individual municipalities had some degree of leeway over how to distribute them, but the rule was that suffrage was based on your fyrktal - a number determined by the amount of tax owed and paid. One fyrk was one vote, and there was no limit to the number of votes one could own. In Gällivare, to take one particularly extreme example, LKAB held 5,000 votes. It was not at all rare for a few rich landowners to have the council quite literally in their pocket.

This was to the liking of mid-century liberals, but as "you get out of government what you pay into it" began to be supplanted by "equal rights for equal duties" as their main credo (and as it became clear that both the councils and the First Chamber that was elected by them would remain under firm conservative control), there were clamours for reform. Arvid Lindman, the most interesting moderate hero in the world, decided to hear the clamours out and then reform the system exactly to his own liking.

So the weighted vote remained, but a hard cap was set at forty votes and uniform apportionment rules legislated. Now, every 100kr (about 3-4000kr in current value) of taxable income meant one vote, up to a threshold (1000kr in the countryside and 2000kr in the cities), whereafter every 500kr got you one vote up until the aforementioned maximum of forty votes. So, in the countryside, the ceiling was hit at 15000kr (just over half a million), and in the cities, the number was 11500 (420,000).

The cities were also overrepresented in the allocation of members, which was done for the county councils (unlike the Riksdag) as a direct function of population - in the countryside, every 5,000 residents equalled one seat, while in the cities, the quota was 3,000. The country was so overwhelmingly rural that the countryside had a large majority anyway. Each city above 6,000 inhabitants would be its own constituency, and the others merged as far as it could be done within the same county.

Rural constituencies were formed from judicial districts (the same units that formed the Riksdag constituencies under FPTP), unless they had more than 30,000 inhabitants, in which case they would be split into equal halves. The only district to be split three ways was Östra Värend, which was made up of two hundreds - no hundred that I know of was split three ways. They would also be merged if their population was below 10,000 - unless communications were so poor as to make it impractical, which is why Karesuando (pop. 1,126) was its own constituency while Jukkasjärvi and Gällivare (pop. 27,174, but both on the railway) were one.

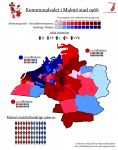

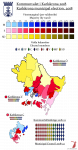

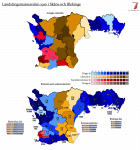

Obviously, while an improvement, this system was still bad news for the Liberals and - especially - the Social Democrats. More than a few counties had liberal majorities counting voters, while the conservative voters were nonetheless able to outvote them because their average vote weight was much higher. This was especially pronounced in the cities, where class divisions were much sharper than in the countryside (or to put it crassly, where the underclass might still earn enough income to have the vote, unlike in the countryside where they were all paid in kind).

Now, the Scanian plains were an exception to this, having a more continental European system of large estates with wage-earning labourers, and the result was that the Social Democrats did quite well there compared to the entire rest of rural Sweden, but still got utterly thumped by the superior vote weight of the other parties.

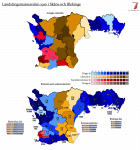

The map below shows only the three southernmost counties, which are the ones I can find handy parish maps of. If I can be arsed, there are also maps of Halland and Kronoberg, but they're going to be so deep blue as to be dull.

To begin with, the 1911 general election was the first in Sweden to be held by PR... or so we're told. In fact, the election law providing for universal male suffrage (nearly) and proportional representation was passed in 1909, and elections to the county councils were held under the system thus established in the spring of 1910. Well, they were held under the system established for local elections, which was a bit different.

Until this point, while the Second Chamber of the Riksdag had been elected by direct, equal suffrage for anyone who passed a tax threshold, municipal and county council elections had operated under weighted suffrage. Any legal person paying taxes to a municipality - whether a person, a company or an economic association - "owned" votes as a product of their taxation. The individual municipalities had some degree of leeway over how to distribute them, but the rule was that suffrage was based on your fyrktal - a number determined by the amount of tax owed and paid. One fyrk was one vote, and there was no limit to the number of votes one could own. In Gällivare, to take one particularly extreme example, LKAB held 5,000 votes. It was not at all rare for a few rich landowners to have the council quite literally in their pocket.

This was to the liking of mid-century liberals, but as "you get out of government what you pay into it" began to be supplanted by "equal rights for equal duties" as their main credo (and as it became clear that both the councils and the First Chamber that was elected by them would remain under firm conservative control), there were clamours for reform. Arvid Lindman, the most interesting moderate hero in the world, decided to hear the clamours out and then reform the system exactly to his own liking.

So the weighted vote remained, but a hard cap was set at forty votes and uniform apportionment rules legislated. Now, every 100kr (about 3-4000kr in current value) of taxable income meant one vote, up to a threshold (1000kr in the countryside and 2000kr in the cities), whereafter every 500kr got you one vote up until the aforementioned maximum of forty votes. So, in the countryside, the ceiling was hit at 15000kr (just over half a million), and in the cities, the number was 11500 (420,000).

The cities were also overrepresented in the allocation of members, which was done for the county councils (unlike the Riksdag) as a direct function of population - in the countryside, every 5,000 residents equalled one seat, while in the cities, the quota was 3,000. The country was so overwhelmingly rural that the countryside had a large majority anyway. Each city above 6,000 inhabitants would be its own constituency, and the others merged as far as it could be done within the same county.

Rural constituencies were formed from judicial districts (the same units that formed the Riksdag constituencies under FPTP), unless they had more than 30,000 inhabitants, in which case they would be split into equal halves. The only district to be split three ways was Östra Värend, which was made up of two hundreds - no hundred that I know of was split three ways. They would also be merged if their population was below 10,000 - unless communications were so poor as to make it impractical, which is why Karesuando (pop. 1,126) was its own constituency while Jukkasjärvi and Gällivare (pop. 27,174, but both on the railway) were one.

Obviously, while an improvement, this system was still bad news for the Liberals and - especially - the Social Democrats. More than a few counties had liberal majorities counting voters, while the conservative voters were nonetheless able to outvote them because their average vote weight was much higher. This was especially pronounced in the cities, where class divisions were much sharper than in the countryside (or to put it crassly, where the underclass might still earn enough income to have the vote, unlike in the countryside where they were all paid in kind).

Now, the Scanian plains were an exception to this, having a more continental European system of large estates with wage-earning labourers, and the result was that the Social Democrats did quite well there compared to the entire rest of rural Sweden, but still got utterly thumped by the superior vote weight of the other parties.

The map below shows only the three southernmost counties, which are the ones I can find handy parish maps of. If I can be arsed, there are also maps of Halland and Kronoberg, but they're going to be so deep blue as to be dull.

Last edited: