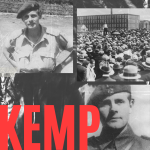

Field Marshal Peter Kemp

Field Marshal Peter Kemp

1950 - 1951

On September 22nd, 1950, in front of the grim entrance of the Gresford Colliery, some 700 delegates representing Britain's mineworkers assented to the founding of the National Union of Mineworkers, a legitimate successor to the old Miners' Federation that had been turned into a shell for compradors and German stooges under Lloyd George. For Peter Kemp, this was a very,

very bad move.

For just under a year, spanning from the warm spring of 1950 to the chill of January the next year, Kemp served as the

de facto ruler of a country that didn't want him and the native liaison to an occupation that didn't need him - tapped by the Americans over more experienced hands to ease Britain back into civilian rule for his partisan exploits in the Midlands, domestic renown for his leadership of the Imperial Defense Army against the German occupation, and his skill in aggrandizing himself with Walter Bedell Smith, Kemp was of the "right stock and temperament" (Smith's words) to manage Britain's transition back into civilian rule. While the freshly-ratified Constitution of the United Kingdom had

technically mandated elections to be held immediately as possible, Kemp and the British National Authority had in turn been invested with the power to call elections and end its transitional rule at its own leisure, the contradiction not lost on the trade unions and various left-wing groups agitating against the American presence on the island.

Despite this, Kemp was viewed with cautious enthusiasm by the British public - as Douglas and Stalin divvied up the smoldering embers of Europe, Kemp intended to do his bit in the new Cold War domestically, focusing on re-establishing the British state and inoculating it against Soviet subversion. With the BBC (still operating out of offices in Montreal, for the time being) and Radio for a Free Britain reporting on the latest atrocities coming out of Berlin and a "black shadow" falling on free peoples from Italy to Hokkaido, the mood was, for the time being, anti-Soviet. The BNA had a crucial window of opportunity to tip the scales against a nascent union movement and what remained of the left-wing Resistance, packing out the British state with Tories returning from exile, pliable businessmen and veterans of the IDA. Kemp, who's former membership in the Spanish Legion wasn't a well-kept secret, could not blow this chance. The "rebuilding of Britain," as Kemp put it in his first public speech formally heading the BNA, was an effort to "win back what we have lost - economic prosperity, social stability, political liberty, in short, the values millions died for in defense of our Isle." A skilled orator he was not, but the hoo-rah sentiment came through nonetheless.

Other matters took immediate priority, however, and the first issue on the docket was the matter of Britain's currency. Operating on American dollars, BNA ration books, formal and informal scrip and mutual aid in the aftermath of Germany's rollback, Kemp saw the re-introduction of the Pound as both a matter of financial necessity as well as patriotic duty. His vision of the "new Pound" was little more than a version of the old, a strong and independent currency that would be used across what remained of the Empire (the word

Commonwealth was viewed with disdain among Kemp's inner-circle), neither tied to the U.S. nor the continent. An independent Pound would best serve the UK in preserving its economic influence within its old sphere of influence, allowing it to check anti-colonial and communist-adjacent movements throughout the world. This idea, to put it lightly, was looked upon poorly by the Americans. The overwhelming amount of funds promised to the UK under the Pauley Plan was, suddenly, conditional - either get with the program, work inside the bounds of dollar hegemony and integrate Britain with the rest of Europe, or Kemp would face the full brunt of his patrons anger. Imperial nostalgia was not useful in the battle against the Reds. The message was received, with the Pound re-introduced as fully convertible to the American dollar, backed by millions of dollars in Pauley Plan counterpart funds. The acquiescence of Kemp, while not unexpected, was not well-received by civilians who were at least expecting some semblance of independence from the BNA

viz Washington.

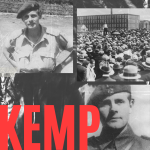

The return of Queen Elizabeth was met with public fanfare and helped revive some public support for the BNA, but things quickly soured from there. It turned out that "re-building Britain" for Kemp meant warm welcomes for former collaborators and the cold shoulder for union men and left-wing partisans. The Emergency Laws, little more than Kemp's personal diktats, set strict regulations on public gatherings and associations, required BNA approval for union organization and union strikes, and instituted severe background checks on those who fought the Germans under organizations with perceived Soviet or Republican sympathies. Resentment at the so-called civilian BNA began growing on all fronts - the Left for obvious reasons, the center for Kemp's dictatorial means of politics, certain sections of the Right for his kowtowing to the Americans and apolitical Britons for his failure to deliver on a rapid economic recovery.

The NUM's foundation, done without the assent of the BNA, proved to be the straw that broke the camels back. September 23rd saw the NUM begin a symbolic occupation of Gresford in protest of the BNA's union policy, which in turn was met by the full force of the Wrexham and Cheshire Provisional Constabularies. The Battle of Gresford was the moment Kemp's position became totally untenable; scenes of officers dressed entirely in black scrapping it out with gaunt miners cemented the feeling of creeping totalitarianism that had set into British society, as impromptu solidarity strikes and protests broke out around the country. Jack Jones, a prominent member of the left-wing Resistance who had on the side opposite of Kemp during the Spanish Civil War, calling for "massive resistance" against Kemp's "khaki fascism" was the point of no return. The anti-communism of 1950 had been replaced by a spirit of fervent radicalism by the end of the year.

Kemp, according to documents discovered in the BNA archives in 1987, fully intended to respond to this public unrest with further reprisals, only for a call from Washington to stop him dead in his tracks. While the contents of their conversation are unknown, its held that President Douglas 'reminded' Kemp that he had a constitutional obligation to call for elections shortly, and that if this was pushed back for reasons of national emergency or in any way meddled with by the BNA, that the United States would have to intervene even more forcefully in Britain's affairs. In a curt, written address to the nation, Kemp announced elections would be held on the 3rd of January, 1951, and that once the results were finalized the BNA would be replaced by the freshly-elected government.

After the BNA was wound down and replaced by Britain's first elected Parliament since 1942, Kemp would retire from politics, working as a lecturer and anti-communist public speaker for the rest of his life. His memoirs were published in a trilogy over 1974 through 1976, covering his time from the Civil War to the IDA. His role in the BNA is largely absent from his writings. Kemp would pass away on a trip to a National Union Party conference held in Calgary, Canada in 1995.